Authentic liturgy educates the inner man

May 10, 2021 | Miles Christi

1) An incessant reminder of divine transcendence, 2) the alluring power of liturgical beauty, and 3) an increase in the “sense of the Church” — these are the great benefits which participation in solemn Catholic liturgy provides, if it remains faithful to the roots of its tradition.

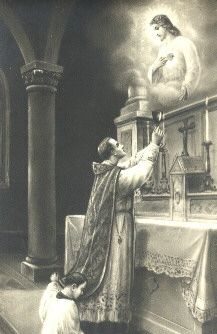

Let us consider that which is most hidden and most secret within us, that which hides itself from view and gives life its meaning, the precious pearl, the treasure hidden in the field, that which the contemplatives search for and, once found, would not exchange for all the gold in the world: the discovery of God within us. The fourth and greatest benefit of the liturgy, and its most profound reason for existing – because sacred beauty is not an end in itself – is the education of the inner man. It leads us with a steady hand into the sanctuary of the soul, where the only drama essential to human existence unfolds: the growth of our supernatural life.

From that immense treasure of symbols, words, and ritual actions we must take the subject of our meditation. Personal prayer has as its theme the very text of the liturgy; it springs up from its womb. Let us, then, be caught up in it, and afterwards continue to draw on what we have gathered during the liturgy. God is reaching down to us at this moment; in silence, let us contemplate the ideas thus suggested. During its celebration, this kind of interior prayer is the most intimate part of the liturgy; and afterwards it becomes its reverberating echo, a precious perfume, a personal fruit suited to the dispositions and needs of each one of us.

This is not only true for religious, but also for lay people. George Bernanos, very much a man of his time, was a living illustration of this: his interior life was drawn to the sources of the liturgy, and he was transformed from a brilliant pamphleteer into a writer of the soul. “Each day he read the newspaper and listened to the radio. However, each morning, no matter what, he set aside half an hour as sacred. Before his family awoke, before the house filled with noise, he would read, in his old, worn missal, the Mass of the day in Latin, with all the concentration of mind and soul he was capable of: this predestined soul had received the divine privilege of attention. He nourished himself avidly with the unchanging formulas of the liturgy, finding in them each morning a note of startling freshness. It was as if, each morning, these words were being said for the first time in the entire history of the world and to him alone. They were his daily and supersubstantial bread. It was in this way that he started his day.” (Bruckberger, Bernanos Vivant)

But the education of the inner man is not solely a result of the calm and recollected atmosphere of the Prayer of the Church. There is the almost sacramental presence of Christ within the mysteries of the liturgical year. The mysteries are the very actions of Christ, such as His Passion, His Resurrection and His Ascension. They were accomplished at a particular point in time and finished for ever with regard to their historicity, but are conveyed and prolonged throughout the sacrificial action, just as the light from a star, extinct for thousands of years, continues to shine in the night. In the same way, in the different mysteries, Christ comes in the course of the liturgical year to meet souls, in order to recreate them in His image.

One sees, then, in the unfolding of the liturgical year, not a cold and inert representation of the life of our Lord, but the irradiation of the very person of the Redeemer, bringing to life in each of the faithful the saving action of His Passion and of His ascent into glory. It is in this way, concludes St. Leo the Great, that that which was visible in the life of our Redeemer has passed into the mysteries: Quod itaque Redemptoris nostri conspicuum fuit in sacramenta transivit.

For the Fathers of the Church, the words mysteria and sacramenta are synonymous. They designate a sacred action in which the work of our redemption is rendered present, not merely as a symbol, but as the ritual conveyor of an ineffable reality.

What a broadening of our perspective and what a deepening of our faith this will imply if we only, by our esteem for the liturgy and for its sovereign efficacy, consent to let it live and accomplish in us the divine work of our redemption!